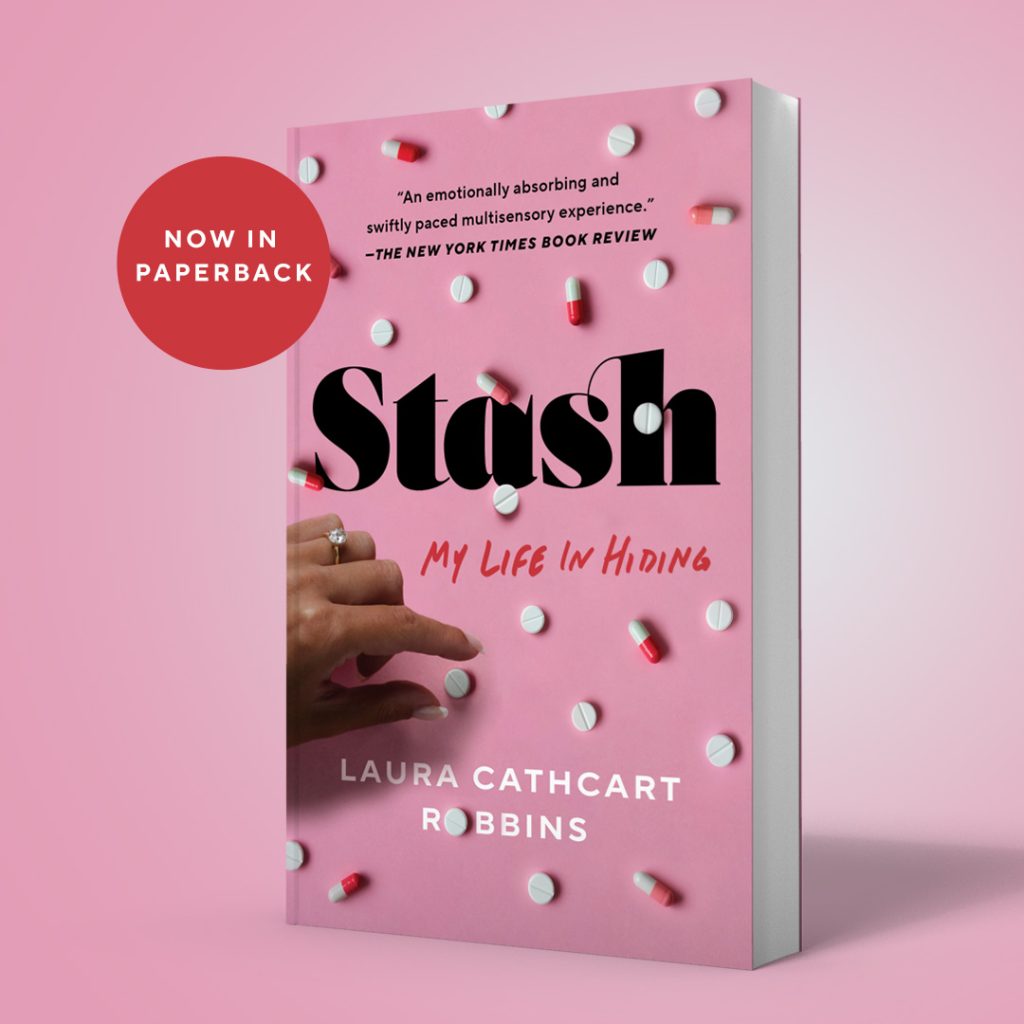

But recovery isn’t easy when you’ve spent your life working to ensure your “brown skin blends in with [your] white, pink, and golden surroundings,” by trying to be “twice as smart and twice as good.” Laura honed this strategy while growing up with her abusive stepfather, Kenny. To survive his torment, she learned to “hide in plain sight” and “give away nothing” that would reveal her weaknesses. For much of her life, this worked extremely well. Despite dropping out of high school and a brief stint freebasing cocaine, she forms a successful public relations firm, marries a prominent Hollywood director, and has two beautiful children. In fact, she hides so well, she’s nominated for PTA president of her children’s exclusive private school while nursing a ten-Ambien-per-day habit.

At times, Laura hides in plain sight within her own story through the italicized interior monologue she embeds within her dexterously written chapters. When trying to score more pills, her prose portrays the “good patient” the doctor expects. “I try to keep my face composed as I search for the right answer… I fold my trembling hands on my lap out of sight and dig my nails into my palms.” But when this doesn’t work, we see past her smile. Herman, that nosy fucker, I should have known he was going to dime on me.

By revealing her shadow self and pulling no punches around her challenges, Laura explores the dichotomies addicts face. You can’t be good and jonesing for more pills. You can’t be successful and an addict. You can’t suffer and be accepted—especially if you’re Black. Her use of interior monologue to explore these dichotomies creates a window into an experience that might seem foreign to many white readers. Yet the intimacy she fosters as she carries us deeper into her world also serves as a mirror into who we are. In sharing her most private self, she forces us to confront the secret selves within us, the times when we compromise, and the emptiness that comes from hiding who we are.

I love her fresh metaphors, honesty, and grit. But sometimes I bristled at Laura’s wealth. Her recovery journey takes place in a world where doctors make house calls, you fly private to rehab, and anything can be delivered. At the height of my mother’s addiction, an empty refrigerator led to more than one “surprise” dinner at grandma’s house. Most of the other addicts I knew were trying to avoid eviction, not looking for pills in their Louboutins. Then I rewatched Chimamanda Adichie’s TEDx Talk “The Danger of a Single Story in preparation for an event I was hosting. As a young writer, all Chimamanda’s stories included scenes with snow and white characters who ate apples and drank ginger beer. At the time, she believed these details defined what a story was.

For many white readers, there’s still a single story of Blackness in America, one that’s largely based on newscasts about poverty, inferior education, violence, and lack. Laura fears these stereotypes so much, entering treatment feels like failure. “It’s official. I’m a Black drug addict mother going to rehab. I’m a cliché like a motherfucker.”

But not all clichés are visible. The lack of representation among BIPOC authors in the Quit Lit genre unwittingly reinforces a single story of recovery that’s steeped in whiteness. That’s why we need Laura’s book. Like the Cosby show of the 1980s that flipped the script on the prevailing stereotypes of what Black families looked like, Stash flips the script on Black addiction, not just by breaking through stereotypes like the destitute addict, but by revealing the unique hardships people of color face when they’re once again the only one in the room.

While watching Chimamanda’s TEDx Talk, I realized I had inherited a single story of what constitutes legitimate suffering. In my rustbelt hometown, we believed only the downtrodden truly suffered. As my education and wealth increased, I often dismissed my problems because they didn’t compare to what I’d grown up with. My love for Laura’s redemption story and the quality of her writing forced me to reckon with that viewpoint, and the toll it has taken. For a long time, my addiction, which came with a withdrawal as wicked as Laura describes, didn’t feel real, because it didn’t live up to my internalized expectations.

Chimamanda says that “When we reject the single story… we regain a kind of paradise.” In accepting the legitimacy of Laura’s suffering and the miracle of her sobriety, I began to appreciate the gift of my own recovery. It’s one of the many reasons I’m grateful for her book.

Source: https://hippocampusmagazine.com/2023/04/review-stash-my-life-in-hiding-by-laura-cathcart-robbins/